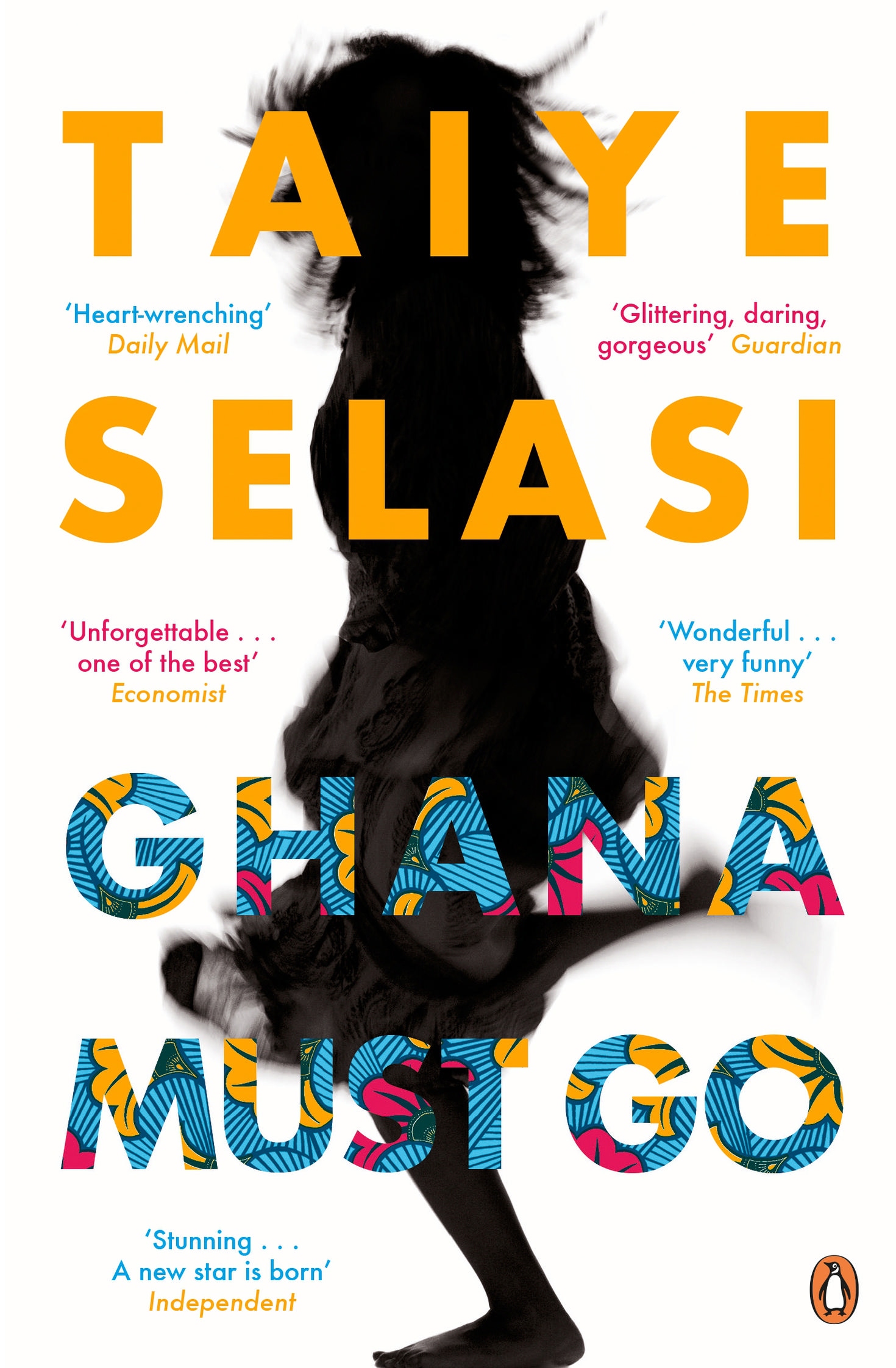

I can’t remember ever having taken such a long time to

read a novel! It has been so terrible that I cannot even recollect how long I

took to read Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go.

I suspect I might have taken well over three months with long stretches away

from the story. A busy schedule would be the easiest scape goat but I must

admit I found the text rather a slow read especially the early pages. But

please do not mistake me, the novel isn’t boring in the sense of the word!

There has been an increase in stories of immigrants

and Ghana Must Go adds to the

statistics. I sincerely pray that African writers are not striving to whet the

appetite of some Western fetish for a certain type of literature. Ghana Must Go is a story of Kweku Sai a

Ghanaian married to Folasadé Savage. Between them, they have four ‘talented’

children: Olu, Kehinde, Taiwo and Sadie. Olu takes after his father by becoming

a distinguished surgeon whilst Kehinde is a famous artist. Taiwo and Sadie have

their brilliant set of skills and the reader could easily mistake the writer

for projecting near perfect children until the story unfolds and we unpack the

various sets of character for each. In the pair of twins, Kehinde and Taiwo,

the reader catches a glimpse of some African mythos but this is hardly explored

any further.

In this story, it is tragic what befalls Kweku Sai at his

place of work. The stark reality of subtle racism and him being a victim of

capitalism in which he is sacrificed to appease a hospital benefactor speaks of

the unfair treatment of immigrants of African descent. Having worked so hard to

earn a reputation and honour, Kweku Sai is unable to reconcile himself with the

job loss nor manage the patriarchal expectations and he results to putting up a

face until the day his son, Kehinde, witnesses the father being ejected from

the hospital in humiliatingly embarrassing circumstances. The event is devastating

for both the son and father and Kweku Sai decides to abandon the family.

Kweku Sai’s job loss and his failure to confront the reality

speaks of his tragic character. He spends a lot of money on his lawyer hoping

to win but miserably fails to get reinstated. Having squandered his savings and

with no energy to seek for a job elsewhere, he chooses to go back home – Ghana.

The wife, Savage, is left with the difficult duty of bringing up the children

single-handedly. One cannot fail to empathise with her especially being privy

to the fact that she forsook an opportunity to pursue law at Yale in order to

support Sai and to bring up their children. Sai’s loss of a lifetime career is

catastrophic but not as devastating as Savage’s sense of betrayal when Sai

walks out on her and their children. The formidable sense of kinship that has

been established in their family teeters on the precipice of tumbling down

overnight.

|

| Image courtesy of google.com images |

Fola’s being left by Sai rekindles bitter memories of

her childhood and the trauma of the loss of her mother and later father. The tropes

of leaving and being left begin to manifest more emphatically in her life with

the departure of Sai. Fola sends Kehinde and Taiwo to Nigeria hoping that they

would attend a better school only to expose them to the destructive life of sexual

abuse of children in the hands of their uncle. Although she had best intentions

at heart, this act fractures her relationship with her daughter, Taiwo, irreparably

since the latter blames the mother of negligence. Sai’s family bond disintegrates

further and the siblings appear to have no human connection with each other. It

is clear that the family is deeply wounded and traumatised but no one is

willing to confront the reality.

When the death of Sai happens, the family has to

confront its demons and travel back to Ghana to lay the father cum husband to

rest: to seek to heal and hopefully rediscover the meaning in life as they reconnect

severed bonds. Throughout the text, the reader feels that the writer glosses

over character’s hurts, emotions and aspirations. There is a sense of shallowness

in the way particular events, occurrences and experiences are handled. For instance,

it is not clear whether Sai remarried or not. Fola’s emotions, dreams and

achievements are masked throughout and overshadowed by those of the children

and the husband alike. Indeed, Fola is not given an opportunity to deal with

her tragic childhood and neither does she get a chance to be openly angry with

her husband; to confront him in person and pour out her anger. The children too

are not allowed to explore their lives deeply and one feels as though the writer

barely attended to their individual reticence.

The novel’s title is borrowed from a historical

political tiff between Nigeria and Ghana in which Ghanaians were expelled from

Nigeria in 1983. However, I didn’t read anything much into this since there is

more focus in the novel on the religious conflict and killings in Nigeria.

In any case, my thoughts about the story are all

jumbled up. I cannot help it now that I spread my reading of the story far and

wide. However, one thing is clear for me: immigrant literature symbolises for

us tropes of leaving, being left – never ending acts of departure. In all this

the reader is warned that nothing is permanent and although we might remain

forever nostalgic about destinations or pasts that we have come from, futures

we may never behold as ours, we cannot ever really feel at home in either of

the places we depart from or arrive at since we are always on the move. In fact,

one can argue that each one of us is an immigrant of sorts in our various

spheres of life. This is a largely symbolic novel reflecting the tribulations

of an immigrant family and their efforts to reconnect severed relationships in

a bid to live normal lives. There is an intense sense of rootlessness,

insecurity, pressure, yearning to belong yet at the same time severely

alienated. However, is there really anything ‘normal’ and what in essence is ‘normal’

anyway? Ghana Must (just) Go!!