Bridging

the Socio-Economic Gap against All Odds

Although

Mwangi Gicheru crossed the bridge of life to death in May 2014, it is

interesting to note that his texts continue to inspire many people to bridge

the gap of literacy though a reading of his novels. Indeed, Gicheru is revered

for titles such as: Two in One

(1970), The Ivory Merchant (1976), Across the Bridge (1979), The Double-Cross (1983), The Mixers (1991) and The Ring in the Bush (2013). From

comments posted on the internet, it is obvious that Across the Bridge has left an indelible mark on the minds of many

as an initiatory text into the world of Kenyan literature.

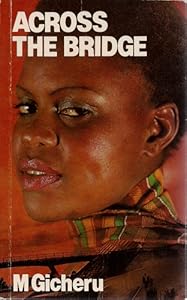

Across the Bridge

narrates the story of two young lovers, Chuma and Caroline Wambui, whose social

and economic worlds are distinctly apart. Chuma is a house boy serving the

family of Kahuthu, Caroline’s father, a civil servant representing the

neo-colonial bourgeoisie or as described in the text a black-duke. In this post-independence

social setting, interactions between employees and family members of their

employer is characterised by a master servant relationship and any cordial

relations or attempts at familiarity are vehemently thwarted. Thus, the rich

neo-colonial suburbs are depicted as ailing from extreme loneliness since

relationships between the servants from different households are also

forbidden.

Caroline

Wambui, Kahuthu’s only daughter tragically suffers from this set up which

denies human interactions amongst the different social classes. As a young

schooling teenager, Caroline yearns for friends both male and female, but the

father’s hawk eye and security detail denies her the possibility to make

friends. Devoid of a human touch, apart from that of her parents, and yearning

to quell the heat of teenage emotions, Caroline crosses the social bridge and

reaches out to Chuma, the only young man within her reach; albeit, the houseboy

with whom she is not supposed to have any second thoughts about.

Chuma

considers himself “A factory reject!” because he “[suspects] God must have

created [him] shortly before lunch. The lunch bells were ringing when He was

making [him]. In a hurry to leave His workshop, He left [him] incomplete. Worst

of all, He gave [Chuma] the brain of a chicken and the body of a human.” This

sense of dark humour pervades throughout the text providing it with comic

relief from the tragic happenings that unfold thereafter. Therefore, in his

self-deprecation, Chuma does not imagine that Caroline would cast her gaze

towards him since the socio-economic setup bars any possible bridging of the

gap between them let alone any physical relations.

However,

as the narrator observes: “It was only natural that Caroline, already an adult,

and beautiful and lonely, would try to seek the company of a member of the

opposite sex.” Consequently, both Chuma and Caroline have to cross the social bridge

since “the only man within [Caroline’s] restricted reach was the only man

within the home compound. The houseboy named Chuma.” Unfortunately, the heat of

their passion for one another is unbridled and Caroline becomes pregnant as a

result of their nightly rendezvous at Chuma’s quarters occasioned by bodily

explorations under the cover of darkness.

The

rest is history. Chuma takes off, Caroline chases after him and Kahuthu is

compelled to sue Chuma for eloping with his daughter. Although Chuma wins the

court case and is determined to keep Caroline as his wife, it is apparent that

he cannot do so within his economic means. Caroline is socialised and

accustomed to a high life that is diametrically opposed to the abject poverty

in Chuma’s home. Realising that he has crossed the bridge to adulthood and

responsibility, Chuma devices all sorts of plans to fend for his wife in a bid

to keep her happy as much as possible.

It

is the pressure from seeing Caroline’s discomfort, her beautiful face becoming

disfigured by the strains of destitution that gnaws at Chuma’s senses and

drives him to leave beyond his economic means. Much later when he has mastered

the art of pilfering money from his boss’s bar in a bid to make extra income,

he blames Caroline for his actions and ambition. He ends up being jailed and

within that period Caroline is reunited with her family and shortly after

whisked far away from Nairobi to Mombasa.

Chuma’s

efforts to track Caroline after his release from jail fuel his desire to

finally cross the economic bridge for good. He contends that Caroline has

planted the seed for ambition in his heart, a feeling that he says he cannot

shake off. Ironically, he gets into bad company with Kisinga, an armed criminal

who argues that there is no difference between what he does and what

politicians do since they are all thieves; thereby justifying his criminal

acts. It is Kisinga who preys on Chuma’s weakness and desire for economic

liberation to induct the young man into the world of crime.

Consciously,

Chuma crosses the moral bridge when he aids Kisinga to clobber a tourist couple

in Mombasa so that they can steal money to finance their way back to Nairobi.

Although Chuma had previously engaged in crime, the reader is hopeful that he

can be redeemed from deteriorating into full-fledged criminal activities, but

after the incident in Mombasa Chuma resigns himself to fate and commits to make

money in any way possible. He rationalises that this is the only way to win

back the love of his life. He even confronts Caroline and accuses her of

planting the seed of ambition in his soul.

A

bank heist in which Chuma is involved culminates in his acquisition of a huge chunk

of money. In his folly to appear important, to be recognised as a man of means,

he makes the mistake of parading himself at a golf club that Kahuthu frequents.

Chuma experiences dire alienation and even begins to hate the new identity he

has forced on himself. This is worsened by his encounter with Caroline who

rejects him even after he has invested so much money to buy her gifts hoping to

impress her. A scuffle in a luxurious tourist resort culminates in critical

injury of Caroline and eventual arrest of Chuma.

Underlying

the narrative are patriarchal insinuations that women are materialistic and

their hearts can only be won with material things. In fact, it appears as

though the text endorses the thinking that women are the cause of men’s

troubles. Although Chuma and Caroline are later reunited, certain moral

questions are left unanswered. Is the narrative suggesting that it is alright

to steal money and invest it in a good cause thereby sanitising the act? Is it

not possible to make money without relying on dirty underhand dealings as is

commonly practiced in most third world nations? Are men incapable of working

hard to make it in life without women as trophies for their hard work?

Across the Bridge

makes for an interesting read by appealing to the popular. It demonstrates the

possibility of love between two unmatched teens by way of a thrilling journey

characterised by setbacks to their quest to stay close. Excitement in the text builds

through their yearning to conquer the insurmountable as both Chuma and Caroline

strive to demystify the thinking that the master’s daughter cannot cast her eye

on the master’s servant. Although Chuma is to blame for pursuing an

unacceptable economic path, the society at large is cast as the main culprit

because it harbours social settings which favour certain people at the expense

of others. It therefore remains for us to see who would not be willing to go

across the bridge of social, political, economic and any other structures that

hinder our progress in our desire for self-actualisation.

I am not yet aware whether any of his texts have transitioned into the movie industry in the form of adaptations. However there was word that Gicheru was working on a script from Across the Bridge before he passed on. It would be exciting to see this alongside adaptations from John Kiriamiti's trilogy.