Teen

literature is often rife with adventure and a spirit of romance. Most texts

that target teenagers teem with narratives that recount escapades, breathless

moments, investigative pursuits and encounters with the unknown world amongst

other aspects. This is best captured through the lenses of Mike Klingenberg, a

fourteen year old boy, who clutches at a lifetime opportunity to make sure that

his life will never be the same again.

Mike

and his classmate, Andrej Tschichatschow, are the typical boring classmates

whom no one wants to associate with. It is even worse for Mike who thinks that

he writes great essays, he can do the high jump better than any other boy in

his class and better still he can draw great images. At least, Tschick is the

odd one out because he is perpetually drunk and he doesn’t care about anyone;

even when the teachers make fun of him he is less interested.

However,

the lives of the two young boys inevitably change when they are denied invites

to Tatiana’s birthday party. It is a big blow to Mike who has a secret crush on

her; he has even drawn a great Beyoncé image for her as a gift. Tschick manages

to drag Mike for a road trip on a stolen car after they have dropped the

drawing at Tatiana’s party rendezvous.

Theirs

is a road trip like no other. Tschick is just learning how to wire cars and has

not mastered the driving skill. Although Mike has been instructed by his father

and left alone at home because his mother has made the umpteenth visit to the

rehab centre, he jumps onto the idea and begins to visualise a world of

infinite possibilities.

It

is a journey that begins from Mike’s home and ends exactly there. Although the

two of them are clueless of where to go, they decide to head towards Wallachia

– a destination that is almost fictitious and non-existent. It is a trip that

comingles with their encounters with dangerous people, reckless driving,

thrilling moments of being free to roam the world and the fear and anxiety of

the unknown when the two of them get lost in mountains and forested areas.

Why we Took the Car

is an exciting story interspersed with moments of suspense. At one moment we

are worried when they run out of gas but a teenage girl, Isa, whom they bump

into at a garbage site helps them siphon petrol. Thereafter, their first

accident results from a reckless desire to outmanoeuvre a police car. Our

breath is held when the car rolls almost a dozen times before it lands on its

roof and the wheels are left spinning in the air. However, the story must

uphold the spirit of heroism. Mike and Tschick survive with minor bruises.

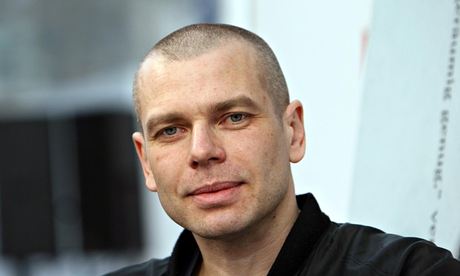

Read more about the author here: http://www.goethe.de/kue/lit/prj/lit/arc/b11/004/enindex.htm

|

| The late Wolfgang Herrndof (shot himself in Aug. 2013 after being diagnosed with cancer in 2010) |

But,

their heroism is short-lived because a few pages later Mike crushes the car

into a trailer ferrying pigs. Although Tschick is taken to juvenile court and

Mike let loose, the boys have learnt their lessons and acquired new statuses

and identities. This is best affirmed when their teacher, Wagenbach is proofed

wrong about their road trip by the arrival of policemen to the school.

The

narrative adopts simple language and uses humour to mock adults. This resonates

well with teenagers because they dislike adults for meddling in their life

affairs. Memorability is enhanced through descriptions like that of the hippo

woman, Isa’s romantic moment with Mike, the countryside etc. It is a novel that

teenagers will definitely love to read.